How the Internet Works

Khinshan Khan

@kkhan01

How the Internet Works

Pfft I know how the internet works, why bother?

Lower Level Understanding

Understanding the internet at a bit of a lower level and recognizing all websites can actually be reduced to the same steps helps us understand more complicated things.

The History

The history of the internet (not from Tim Berners Lee time but sure if you want…), helps us understand why and how certain things like docker, digital ocean, and aws came to be.

Meet Bob

Bob is sort of the user we'll follow.

He could be you or I or anyone else. He's just a person accessing the internet to view webpages.

Meet Company XYZ

Company XYZ is more or less a placeholder for a random company that has a website.

We'll look at what they have to do to host their website so Bob can interact with it.

Common Companies I'll Use

I'll probably make them Google often because https://www.google.com is a site we're familiar with.

I'll also use a small flower chain or taco cart as other companies.

What Happens when we Visit a Website?

Steps:

- Open your device (pc/ laptop/ mobile).

- Open a web browser (firefox, google chrome, etc).

- Enter the URL.

Visit a Website

Let's say we navigate to google.com.

How does our Browser Know?

Our browser somehow automagically figured out the logo and search bar and everything else.

To understand this, we have to understand the role of a browser –>

ELI5 Browser

A browser can be boiled down to 2 functionalities:

- Make requests

- Parse and render files

Let's go Local

Let's save this into a file like hello.html

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8"/>

<title>Hello</title>

</head>

<body>Hello there.</body>

</html>

Now let's view it!

Copy the path eg

/home/shan/hello.html

(it'll differ per OS and user and where you save…)

and paste it in the address bar in your browser!

Let's try some Pizzazz

Let's view this (I know… center is deprecated but still supported by every browser mkay? 🙄):

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8"/>

<title>Hello</title>

</head>

<body style="color: salmon;">

<center>Hello there.</center>

</body>

</html>

Requests?

At this point, we're convinced that the browser parses and visualizes files.

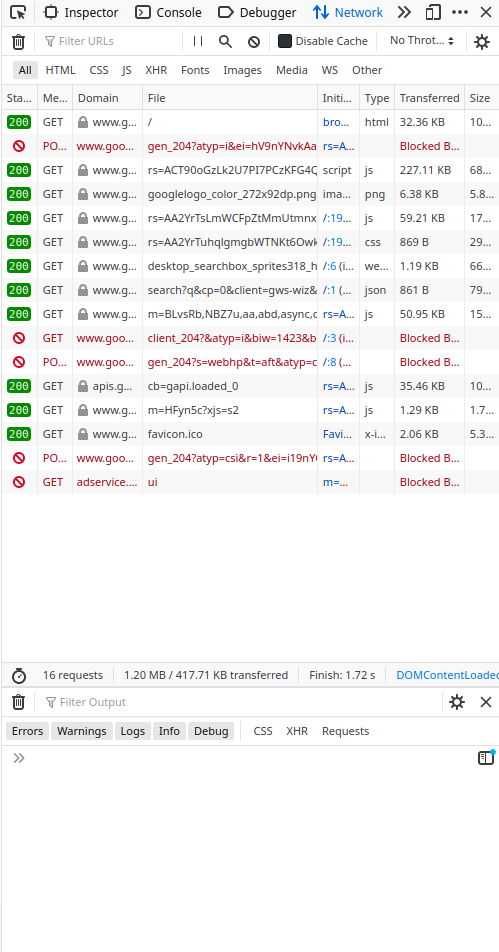

But what about requests? Well, open up your inspect element and head over to the network tab and reload hello.html!

Where does the HTML come from when not Local?

But we don't have any of that data saved on our computer, so how did the browser get the HTML for google.com?

ISPs and DNS

When we throw in google.com in our address bar, that query goes

browser -> ISP -> DNS

and the DNS performs a lookup for its address and returns something like 172.217.0.0 (Google has many IPs)

browser <- ISP <- DNS

Think of a DNS somewhat like a phonebook… if you still remember what those are 😅

Next

Next, your browser makes a request directly to Google's for the HTML.

Requests requests requests!

For now, we'll focus on GET requests, but they're just easier to talk about.

What is a request?

Basically everything connected to the internet has its own IP address.

Via the address, it can expose endpoints which server up information depending on how they're invoked + its implementation.

Just as we were able to get HTML from our local filesystem, a simple apache server can expose the filesystem such that instead of your prefixed root path, it'll be ip address/path/to/file

Pattern

The pattern more or less is as follows --

-

Look up address

browser -> ISP -> DNS -

Get address

browser <- ISP <- DNS -

Get file

browser -> ip address + route -

Get more files

rinse and repeat 1-3 as the page requests or you visit another page ♻

Status Codes

Status Codes Explained

The codes are in hundreds. You're probably already familiar with some like 404 for a page not found.

- 1xx: Informational

- 2xx: Success

- 3xx: Redirection

- 4xx: Client Error

- 5xx: Server Error

The google.com Requests

TB to the that visit to google.com

$cenario

Now, if you're running a website, let's say you're doing it for profit. You have some model that has customers visit your site

Eg: A taco cart is selling tacos 🤨

How does it go down?

Like we've learned, every site follows the same pattern of requests per user.

What happens when many users visit your website at once?

Consequences?

You may not be able to handle a lot of users due to server limitations… you lose out on customers + other customers may have a bad experience 😱.

But we want $

There are a few ways to handle more customers.

The $ costs $$$?

There are a few costs and responsibilities associated with having your own server room:

- cost of actual hardware ⚙

- space to hold the hardware 🖥

- wire management 🙄

- keeping proper temperature 🌡

- electric bills ⚡

Give Responsibility Away!

This is how VPS came to be.

Basically someone owns data centers and farms and has a bunch of machines running anyways, so they rent out some to users.

VMs

I'm not totally clear if VMs came first or VPS, but users would want to run multiple things OS dependently which meant they would need multiple machines… or did it?

VMs basically virtual-izes OSs such that it has its own CPU, memory, network interface, and storage from your one setup.

This lets you either switch seamlessly or potentially have both running at the same time $$$

Containerization

VMs probably led to the evolution towards containerization.

The idea is maybe your programs can share more lower level things and sandbox differently.

Okay Okay, Show me Severless!

So, time for another scenario to see why serverless: a flower chain selling flowers 🌺

For this chain, let's say it doesn't only sell to one location like the taco cart may have.

Day to Day Usage

Your traffic may be low on some days but spike during Valentine's Day.

You're paying needless $$$ 😱

Automagical Servers

Maybe… just maybe… servers can scale up and down as needed.

This gives rise to AWS and GCP.

Another Meme